How Corporate Consolidation Affects Row Crop Farmers’ Everyday Lives and Decisions

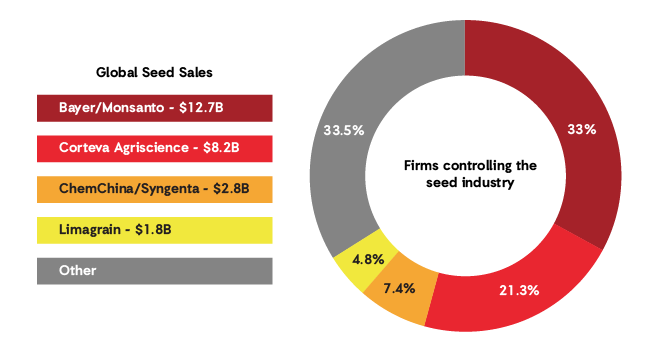

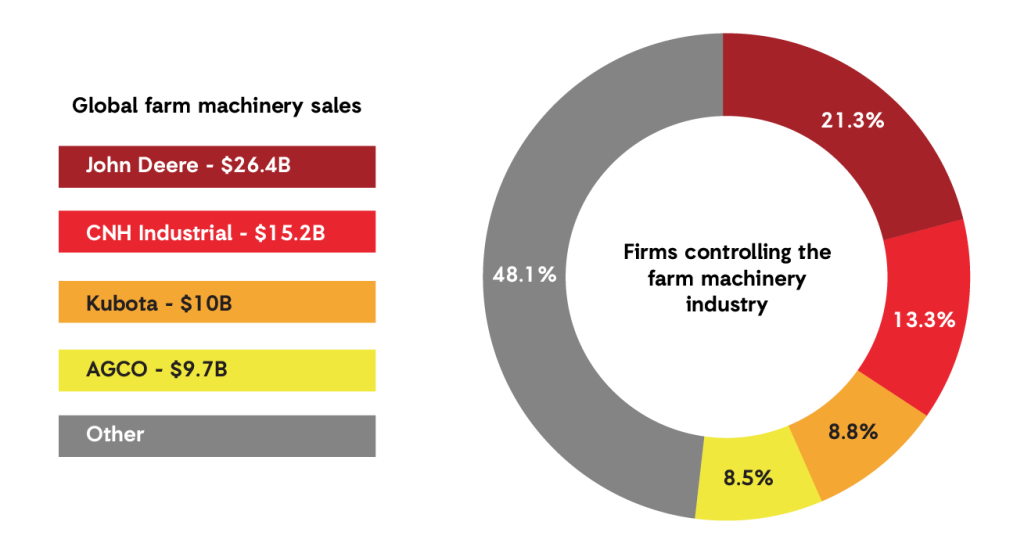

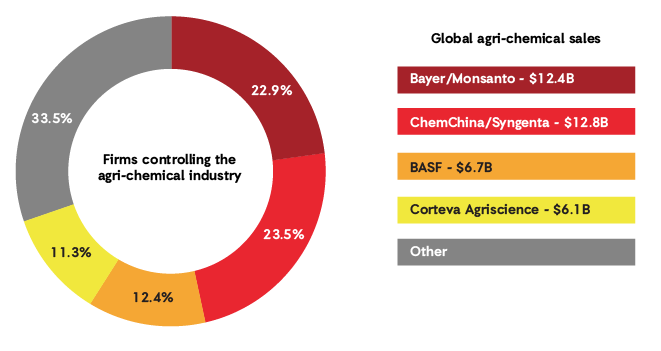

From seeds to herbicides to tractors, the companies that farmers interact with on the day-to-day have gone multinational, consolidating their economic power.

Four companies control 66 percent of the seed market and 70 percent of the agricultural chemical market globally.

Four companies dominate at least half the global farm machinery market worldwide.

With little competition or government regulation keeping them in check, these vast companies can set prices and policies for their products – and have ultimately shaped the farming landscape in the U.S. in order to create maximum profit for themselves.

For farmers on the ground, the consolidation of these industries impacts their lives and livelihoods in large and small ways every day.

You grow non-GMO corn and soybeans near Churdan, Iowa, and just recently, you’ve been converting half your farm to organic.

You and your partner are also raising oats, apples, and hay.

As a row crop farmer, doing business with highly concentrated companies limits your choices and affects everything from your business decisions to the local environment and community.

Corporate control of seeds means farmers have much less control over their farms.

As a non-GMO farmer, you’re limited on what seeds you can choose. It’s harder and harder to find what used to be called “conventional” beans – those that aren’t genetically modified (GMO).

When the seed companies focused on developing GMOs, Monsanto, for example, put all of their good soybean genetics into just those seeds and took its best conventional seed off the market. The varieties that were left on the market really hadn’t been developed like they should have been. When the seed isn’t up to par, it hurts your bottom line. You have to grow more to get the same return.

When you can find it, conventional beans are cheaper than GMO seeds – as much as one-third of the cost of the GMO stuff. For those that use them, the companies that make GMO seeds keep increasing the price every year – even though the genetic modification process hasn’t changed much in 20 years.

It’s always a chemical solution from the big seed companies.

The vast majority of land around you is farmed with GMOs, where chemicals are absolutely necessary. Whatever problems your neighbors might have on the farm, it’s always a chemical solution from the big chemical companies. It’s clearly unsustainable, and you see that it is very damaging to the environment around you.

Monsanto genetically modified both the corn and soybeans to withstand RoundUp, so farmers were hitting these weeds with RoundUp two or three times every year. Because their crops are resistant, they can spray a lot. You can imagine that, eventually, the weeds would become resistant.

If you or another farmer tries to farm a different way – growing different crops or farming without as many chemicals – you run the risk of being less profitable or even losing money. And since you and most farmers you know rent the land you are farming, if you aren’t making enough to pay the rent, then the landowner could rent that land to someone else. Competition forces everybody to basically do the same thing.

Corporate concentration in the agri-chemical industry…

4 companies control 70 percent of the global agrichemical market (Source).

In the next 20 years, corporations will own all the land around you.

In your neighborhood, the generation ahead of you has passed away, and one big operator has bought up their land. Quite a lot of that land had been in pasture, but it was bulldozed in, and the creeks were covered up. It’s all being row-cropped now.

You went through the 1980s farm crisis with one neighboring farmer, but he had a little inheritance afterward that helped him grow. His two boys are in their 40s, and now they’re running the farm operation. They’ve probably got 20 years left. But when they decide to wind down the farm, investors will buy it. That’s all there is left after that generation. There won’t be farmers coming around to buy it because there aren’t any farmers left to speak of.

So in the next 20 years, the land will be corporate-owned. They’ll hire someone to come push the buttons on the farming equipment and watch it from the office on a screen. You don’t have to know the land to do that.

Corporate control over farmland

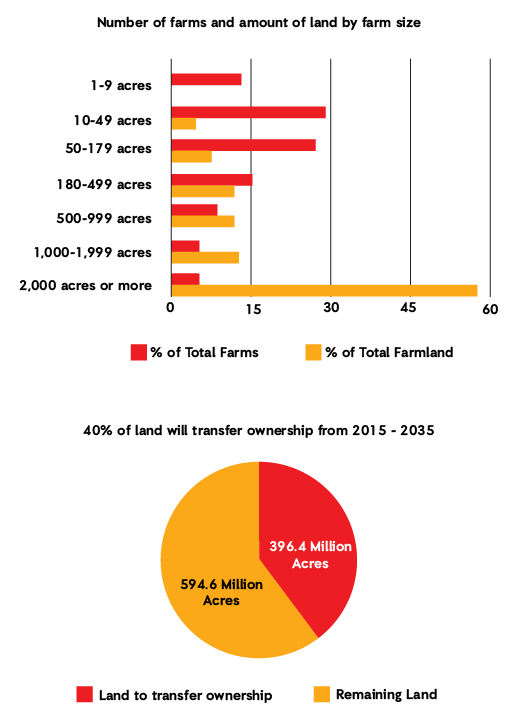

In 2017, the largest 4 percent of farms (2,000+ acres) controlled 58 percent of all farmland, while the bottom 13 percent of farms (<10 acres) controlled just 0.14 percent of farmland (Source)

40 percent of farm and ranch acres in the 48 contiguous states, which amounts to almost 400 million acres, are expected to change hands from 2015 to 2035 as an aging farmer population retires. (Source)

Corporate control of grain processing has driven overproduction and cheap prices, which have pushed farmers into monoculture farming.

You sell pretty much everything at harvest time. The prices you get for selling your corn and soybeans have been low for a long time. They are so low that you can’t even cover your cost of production. You need to rely on different crop insurances and other federal farm programs to make ends meet. You take your money, take your losses, and then you hope that next year will be a little bit better.

The way it used to be was that if prices for corn or soybeans were too low, then you could feed those crops to your animals. And when livestock moved off the family farm and into CAFOs, farms lost use for grass and for other grazing crops like clover and alfalfa. That meant that you lost your sustainable crop rotations.

So now, your community is filled with huge farms raising corn and soybeans to feed millions of livestock in great, big factory farms and feedlots.

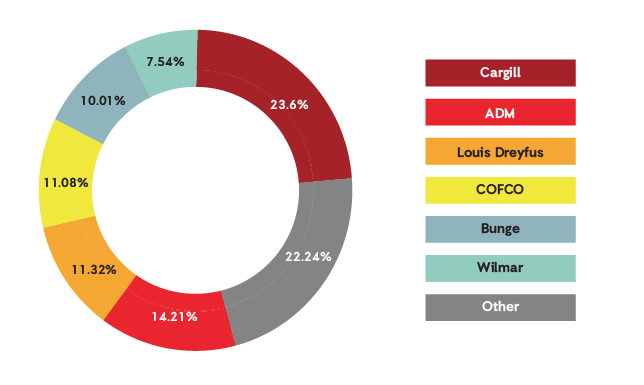

Corporate control over grain processing and trading

The top 6-grain trading corporations control as much as 75% of the global grain and commodities.(Source)

Corporate control over machinery has made farming bigger and bigger and put farmers into debt.

Most farmers are in debt because of the land or machinery they bought. But you don’t have a lot of debt because you just haven’t bought new equipment. Your partner complains about it. They say, “All I have is junk!” It can take a lot of work to keep the old equipment running, but it would cost over $500,000 to buy essential equipment like a new tractor, combine, planter, and disc.

There still are independent places that can work on things, but they are disappearing. The really new machinery needs proprietary equipment and software to diagnose and fix it. You get stuck with the dealer.

Your big tractor wouldn’t start one morning. You called the dealer, they sent someone out; he put his gizmo on to check it out and told you that you needed a whole new diesel injection pump. It was going to cost $7000 – $8000, but that was too much. Luckily, you knew to call a truck mechanic that specialized in these kinds of engines, and they said you needed a module that only cost $3000! That is still a lot of money, but it’s a lot less. That’s the kind of crap you get when you don’t have a lot of choices about who can fix a tractor.

Corporate control over agriculture has destroyed rural communities.

Rural areas and small towns are aging, everyone’s getting older. Not many young people are moving to little towns in rural areas, so it just continues to empty out. If people continue to think the policies in place now are going to change that, they’re wrong.

Your fear is that if the country keeps going the way it is – getting rid of family farmers, replacing them with corporate farms, with big animal feedlots – you’re going to end up making Iowa and all the other rural states that have a large agricultural base, sacrifice zones. Biodiversity, clean water or clean air, community, all those things will be sacrificed just to produce as many cheap commodities as you possibly can for the benefit of big multinational corporations.

Do people really want four big companies determining who will eat and who won’t?

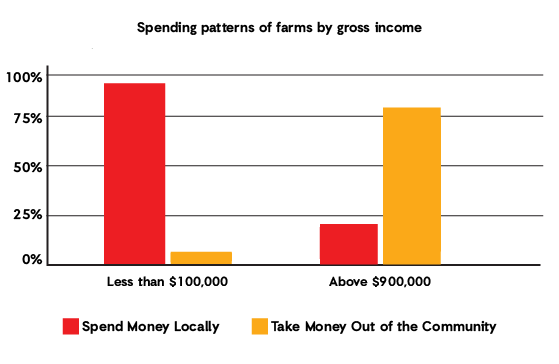

Corporate control over the rural economies

Farms with gross income below $100,000 are likely to make 95% of expenditures locally, while farms with gross income above $900,000 spend less than 20 % locally.

Farmworkers working for corporate factory farms earn 42% less than all other wage and salary workers; 1/3 of farmworkers over 25 years old have annual incomes less than $15,000. (Source)